The great Italian American film director Frank Capra was fond of saying that it was important to “not merely follow trends, but to start them.” Acting on his own advice, Capra directed such classics as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, It’s a Wonderful Life and It Happened One Night.

Through his impressive filmography, Capra managed to pioneer two of the most successful film genres of the 20th century, the romantic comedy and the feelgood film.

This, in turn, cemented his legacy and made of him one of the uncontested titans of world cinema. His achievements now stand as an example for would-be filmmakers around the world. Push the envelope, set the trend, and thus become immortalized.

The Importance of Management Philosophies

Mr. Capra’s advice, however, has much broader applications than in cinema alone. Think for instance about the history of western capitalism. Over the course of the past 120 years, we have seen the sequential rise and fall of various mega-corporations.

Each of these corporations, from Henry Ford’s eponymous Ford Motor Company back in the early 1900s up until Apple Inc. today managed to rise above its competitors. This allowed them to utterly dominate the narrative of its respective period.

The primary questions this incites then, are twofold. Firstly, how did these corporations manage to outcompete their peers so thoroughly for a while? Secondly, what eventually caused them to fall out of favour and lose their dominant positions?

Learning from Successful Corporations

The answers to these questions are multi-faceted and extremely complex; but it surprises no one that management philosophy was a key part of the success of these corporations.

In their prime, the management philosophies of these big corporations allowed them to invent trends. Through innovation, they mined these for tremendous profit. Eventually however, other firms begin to emulate the management principles that set the dominant corporation apart from other firms in its age. When enough others do this, the source of its competitive advantage wears down until the firm’s competitors catch up.

While developments such as this are obviously not pleasant for the dominant corporation, they do have a net positive impact on our economy. By acting as an incubator for a new management philosophy, which can then slowly trickle down into the rest of the economy, the dominant corporations help raise the bar for all of us. The gains are particularly great for the first followers, who integrate the management principles from the dominant corporation into their own operations before others manage to do so. These first followers do not have to run the risk associated with developing a new management philosophy but can profit from the insights produced by the dominant corporations before most other firms.

Looking Eastwards

With this introduction out of the way, it is time to shift our gaze eastwards. One of the most significant macro trends of the past two decades has been the rise of the People’s Republic of China. What was once an impoverished state has first grown into the factory of the world. Now, China is one of the most technologically advanced nations on earth.

The Rise of China and its Management Philosophies

Many Chinese companies are yet to become household names in the west. Most of them have focused their attention on the vast domestic markets of China proper. This is about to change however (e.g., think of the massive number of Chinese EV companies like BYD, SAIC Motors, Chery Automobile, etc.) and is already causing tensions to rise rapidly as western economies seek to adapt.

Sidestepping the thorny issue of geopolitics for a moment, it would be wise to highlight just how unique of a situation we are facing. During the last century, almost all dominant corporations have been American. It was thus mostly American management values and principles that got exported to the rest of the world.

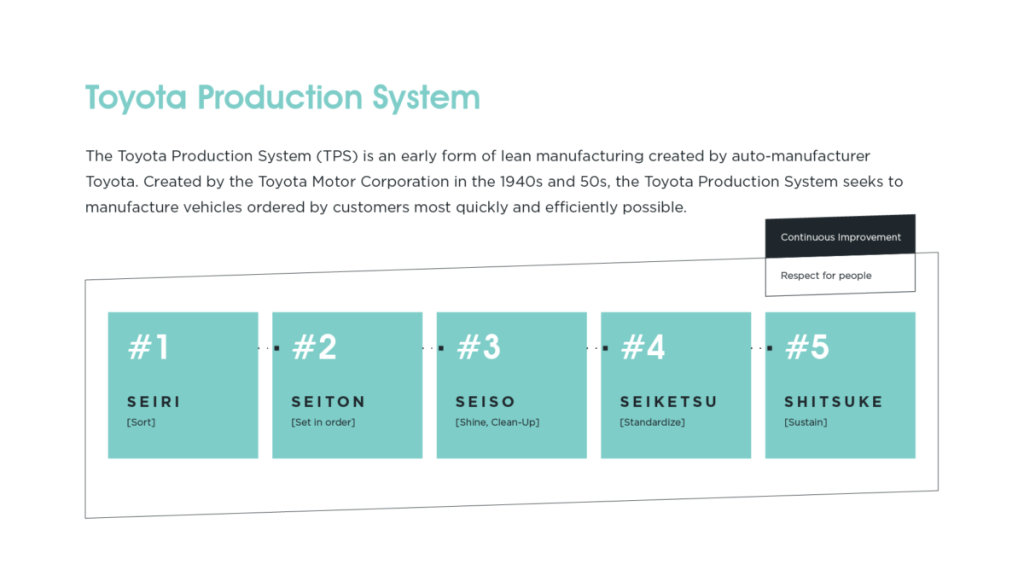

This intellectual monocultural was only really challenged once, during the heyday of Japan Inc., when every big western manufacturing company wanted to emulate Toyota’s fabled production methods.

As the enduring popularity of lean manufacturing and TPS proves, there is an argument to be made that exchanging management and organizational principles across cultural boundaries (and geopolitical rivalries) can be a source of enduring value creation.

We should therefore see the rise of China not only as a threat, but also as an opportunity to learn from a management culture that is distinct from our own. If the example of Toyota is anything to go by, this will allow western firms to integrate the best aspects of Chinese management philosophy and use it as a source of competitive advantage over peers that remain stuck in their ways.

Digitally Enhanced Directed Autonomy (DEDA)

If we want to be able to do this however, we need to first understand what the dominant corporations in China are currently trying to do. There are a tremendous number of China watchers in the world. Most focus primarily on the Chinese political landscape. Relatively few are putting Chinese firms under the loop.

The Three Core Tenets of DEDA

Amongst those select few who do, there is currently a lot of excitement about DEDA. This acronym stands for Digitally Enhanced Directed Autonomy. Together, they sum up the management approach of many of the leading Chinese firms.

This inherently agile philosophy is built around the following three core tenets. We describe each of them in more detail below:

- Granting employees autonomy at scale.

- Underpinning this autonomy with specialized digital platforms instead of middle management.

- Coupling autonomy with single-threaded leadership.

Autonomy At Scale

The first principle revolves around autonomy. At first glance, this is not something altogether new. The desire for more autonomous teams has been with us for a while. The Chinese approach to autonomy distinguishes itself from the classic conceptualization of autonomy in the West. It does so by putting the focus on scaling autonomy up.

This might go as far as units made up of several dozen people a large degree of autonomy. Of course, this autonomy does come with some strings attached. It is neither complete, nor is it given to every single person. Instead, the autonomy is directed towards a specific goal. This often means that client-facing teams end up getting more autonomy. Their proximity to the consumer lends itself more towards this sort of autonomous set-up since it can be built on their deep experience of customer needs.

In practice, autonomous teams start small, but can grow as long as they achieve high marks on certain predetermined goals. These are set by the overarching management of the autonomous teams. For such a system to work, a highly entrepreneurial culture needs to be fostered. This is achieved by creating a proper incentive structure to ensure that success is rewarded.

A good example cited by Greeven, Xin and Yip (2023) is that of Hstyle. A fast fashion apparel brand and part of the Handu e-commerce group, Hstyle’s tremendous success in its home market is often ascribed to its commitment to autonomous operations for its product teams.

As the product teams are closest to the consumer, Hstyle has delegated the responsibility of designing, producing, and selling their products to these teams. Every product team starts out with a minimum of three people. One designer, one sales specialist and a planning and production expert. These can grow exponentially if a product line turns out to be a hit with customers.

Performances of all of Hstyle’s teams are assessed daily (KPI’s include for example sales, gross profit, and inventory turnover). These assessments are then transparently shared across all employees. This creates intense internal competition that puts teams under pressure to deliver.

Those that do will get financially rewarded. Performance-based pay is nothing new of course, but what makes Hstyle’s approach so inspiring is its focus on continuously spinning off new teams to create new products. When a new team starts operations, the leader of the new team is obligated to compensate the original team for nurturing the acquired staff. On top of that, the company’s financial system automatically transfers 10% of an acquired staffer’s bonus to the original team leader every month for one year. In other words, a team leader has all the incentives in the world to nurture their employees’ ambition and help them advance their careers and thus Hstyle’s business.

Naturally, many of the lessons seen in the Hstyle example can also be put into practice in Western firms. To embrace this aspect of DEDA, companies should shift towards a new decentralized leadership model. This new model should encourage leaders to focus on coaching and nurturing talent rather than commanding.

It also entails adopting a new compensation model, where a premium is placed on entrepreneurship (for instance by emulating the spin-out compensation seen in the example of Hstyle) and investment in digital technologies needed to monitor and communicate results across the entire company.

An added advantage of this move towards decentralization is that it circumvents many of the morale problems that plague organizations in this era of low retention rates and increasing staffing shortages (i.e. the infamous great resignation). Allowing teams to create their own inspiration and self-reinforce does wonders for the firm’s position on the Morale / Cohesion Matrix.

Underpinning Autonomy with Specialized Digital Platforms Instead of Middle Management

Like Western firms, Chinese companies use a three-tiered organizational structure. Such a set-up is traditionally assumed to increase responsiveness and efficiency. It consists of a back end (i.e., long-term assets like factories or warehouses for example), a front end (all interactions with partners and customers are done here) and a connective middle system that aligns both.

In Western firms, the connective middle system consists of middle management. All the bureaucracy and factional infighting that this most unhappy group is often prone to tend to wreak havoc on the capacity of the standard firm to make good decisions.

In the Chinese firms that inspired the DEDA acronym, there is a tendency to limit the human element of the connective system to a minimum. Instead, these firms opt for a far more direct connection between the front end and the back end. To enable this, they use digital platforms that centralize access to shared data, services, and other capabilities.

By cutting out the bloated layer of middle management, Chinese firms tend to be far more responsive and fast-paced. Minute signals gathered from customers by front-line staff can be turned into actionable objectives quite easily. In this way, DEDA is an inherently agile management philosophy.

Such an approach also creates a fertile environment for open innovation. The transparency and ease of connecting ideas with the right resources within the firm both stimulates people to experiment and increases the chances of successful outcomes. As great proponents of the idea of Open Innovation, we can only encourage companies to adapt these sorts of digital platforms.

Finally, another advantage of this digital approach is its traceability, as senior managers can monitor in intricate detail how frontline employees perform and which resources and capabilities they use in the pursuit of their objectives.

The most famous example of this part of DEDA is probably the internet juggernaut Alibaba Group through its creation of Zhongtai (Greeven, Xin and Yip, 2023). This is a digital middle office, which has become the gravitational centre of its organizational structure. Maintained by cross-functional teams and overseen by the CTO, Zhongtai hoovers up data from all the various Alibaba platforms and affiliates (e.g., Alipay). It then uses the date to ensure its responsiveness to the needs of the many different stakeholders within the Alibaba ecosystem.

Out of all aspects of DEDA, this one might be tough to implement for Western firms saddled with legacy IT systems and layers of middle management that are unwilling to make themselves obsolete.

The first step, however, is to further speed up digital transformation. The more business processes are digitized, the easier the move towards a Zhongtai-like digital middle office will end up being.

Coupling Autonomy with Single-threaded Leadership

The last core tenet of DEDA is its focus on the proper execution of tasks. To facilitate this, Chinese companies have embraced the idea of single-threaded leadership. First pioneered by Amazon, single-threaded leadership begins with the realization that focus is incredibly important to get tasks done.

Unfortunately, it is extremely hard to maintain focus as a modern manager. Instead of allowing our managers to focus, most Western firms dump too many (often conflicting) tasks unto the shoulders of management. This causes distraction, which in turn leads to a loss of efficiency and efficacy.

Single-threaded leadership then, seeks to counteract these negative trends by giving each leader a S.M.A.R.T. business objective to focus on. With a clearly defined task, budget, and timeline to stick to, managers can throw their full intellectual weight into successfully completing a task.

Again, we find an interesting example in Greeven, Xin and Yip (2023). During the pandemic, EV manufacturer BYD saw its production grind to a halt due to a mask shortage. The CEO thus decided to task his key leaders with quickly finding a way to produce surgical masks to help combat the pandemic and protect BYD employees.

In only a fortnight, the chosen key leaders were able to reassign staff and production materials idled by the pandemic. All of these resources were redirected towards the production of masks. This would eventually turn into a highly profitable side hustle for the company, ultimately netting the company 640 million USD.

To systematically implement single-threaded leadership, Western firms will first have to undergo a change in mindset. Performance evaluation systems will have to become more flexible to allow for temporary assignments. On top of that, there should be active investments into a consistent boomerang policy.

In essence, it will be crucial for firms experimenting with single-threaded leadership to integrate leaders back into the normal structure once their single-threaded assignment is over. Otherwise, no ambitious leader in their right mind would volunteer for a single-threaded position, as it would entail the kiss of death for their career aspirations.

Three Key Takeaways for Integrating DEDA into Western Management Philosophy

To wrap up this article, it is essential to note that Chinese and Western firms differ on a great many aspects. Three of these differences were especially important to create an environment in which a new management philosophy like DEDA could grow:

- China’s firms have cultural DNA that is vastly different from that of Western firms.

- China’s firms benefit from not having expensive legacy IT systems.

- China’s firms had more room to experiment due to the relative cheapness of Chinese labour.

Despite these inherent differences, many exciting lessons can be drawn from these Chinese examples. The three key DEDA take-aways for any western firm looking for their next source of competitive advantage are:

- Autonomy can only truly revolutionize operations if it is scalable and directed at a specific goal. Leaders need to set clear strategic goals for teams to achieve. Incentive structures should focus on rewarding team leaders for growing their core business and helping young talents within their team to spin out new intrapreneurial ventures.

- A digital middle office creates a more structured, immediate, and direct connection between employees and upper management. By utilizing a digital platform that can centralize access to shared data, services, and other capabilities decisions can be taken faster and with more accountability.

- Single-threaded leadership provides essential managerial focus. To properly capture benefits from this approach, western firms need to become more adept at detaching and re-integrating leaders on focused assignments.

To conclude, the economic and business climate in China gave rise to the circumstances necessary for the development of DEDA management. However, the continued digital transformation of Western firms is bringing us to a point where they too could experiment with a systematic DEDA approach to outcompete their more apprehensive peers.